Thank you Franklin Karp for sharing this story with me.

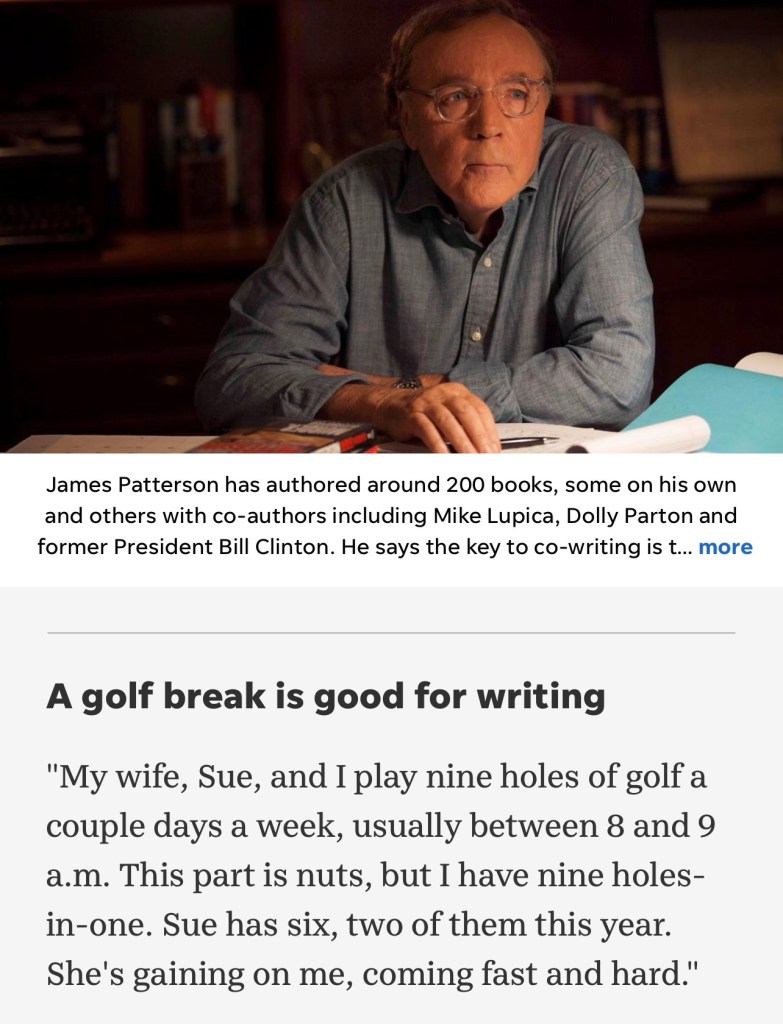

Ken Fritz turned his home into an audiophile’s dream — the world’s greatest hi-fi. What would it mean in the end?

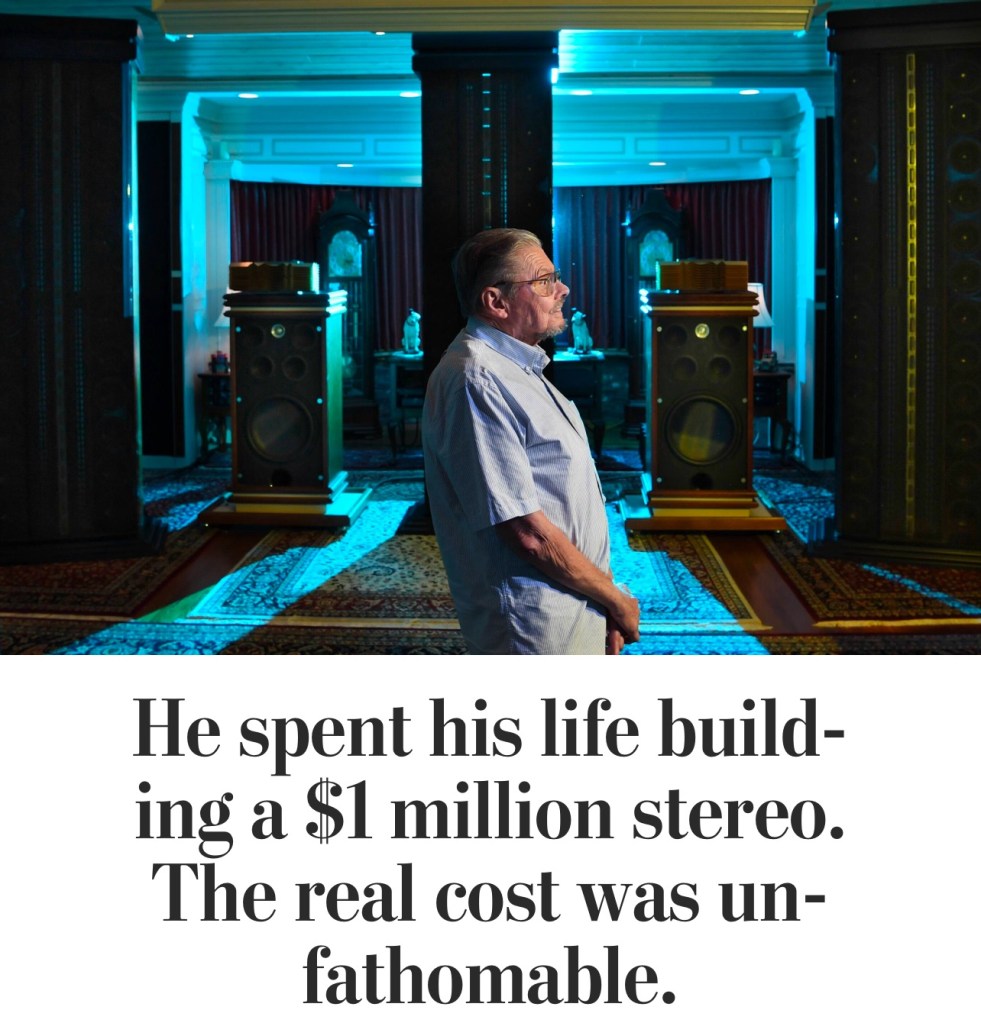

Ken Fritz was years into his quest to build the world’s greatest stereo when he realized it would take more than just gear.

It would take more than the Krell amplifiers and the Ampex reel-to-reel. More than the trio of 10-foot speakers he envisioned crafting by hand.

And it would take more than what would come to be the crown jewel of his entire system: the $50,000 custom record player, his “Frankentable,” nestled in a 1,500-pound base designed to thwart any needle-jarring vibrations and equipped with three different tone arms, each calibrated to coax a different sound from the same slab of vinyl.

“If I play jazz, maybe that cartridge might bloom a little more than the other two,” Fritz explained to me. “On classical, maybe this one.”

No, building the world’s greatest stereo would mean transforming the very space that surrounded it — and the lives of the people who dwelt there.

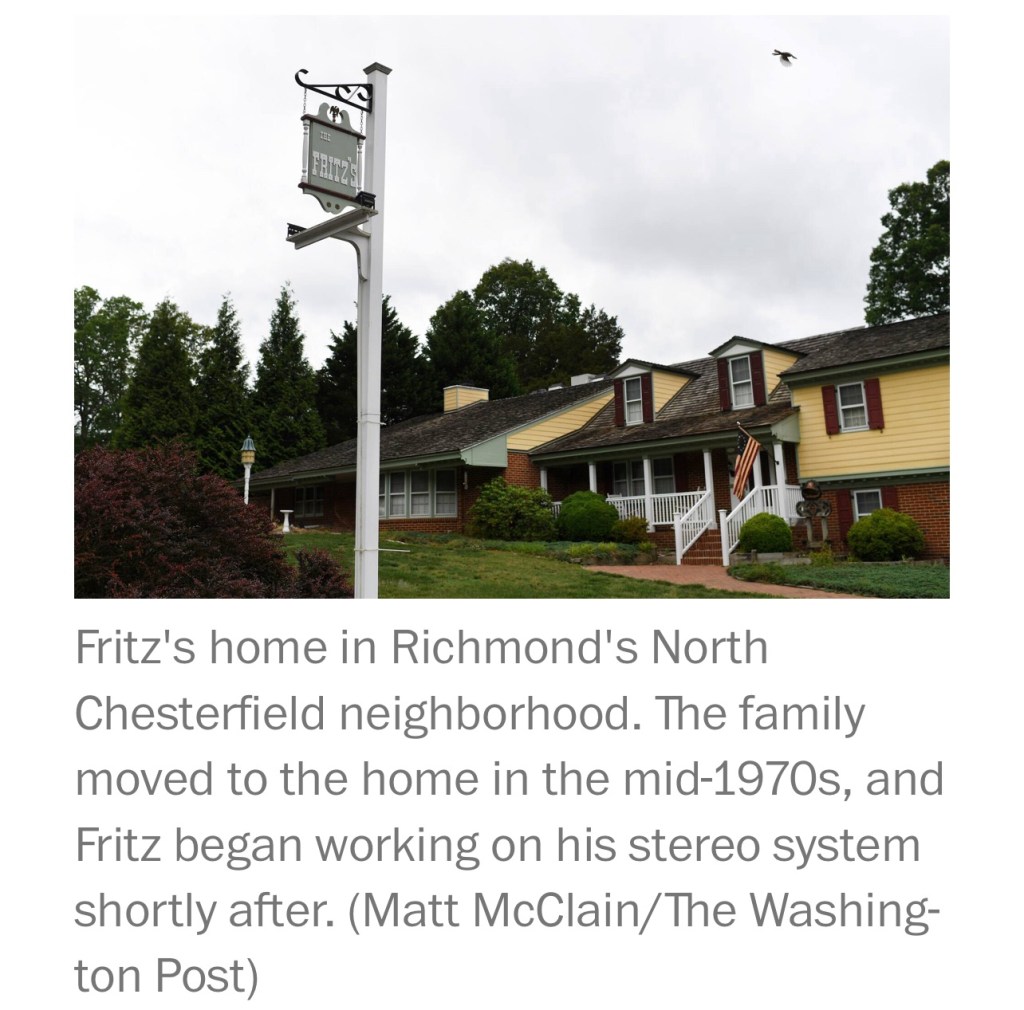

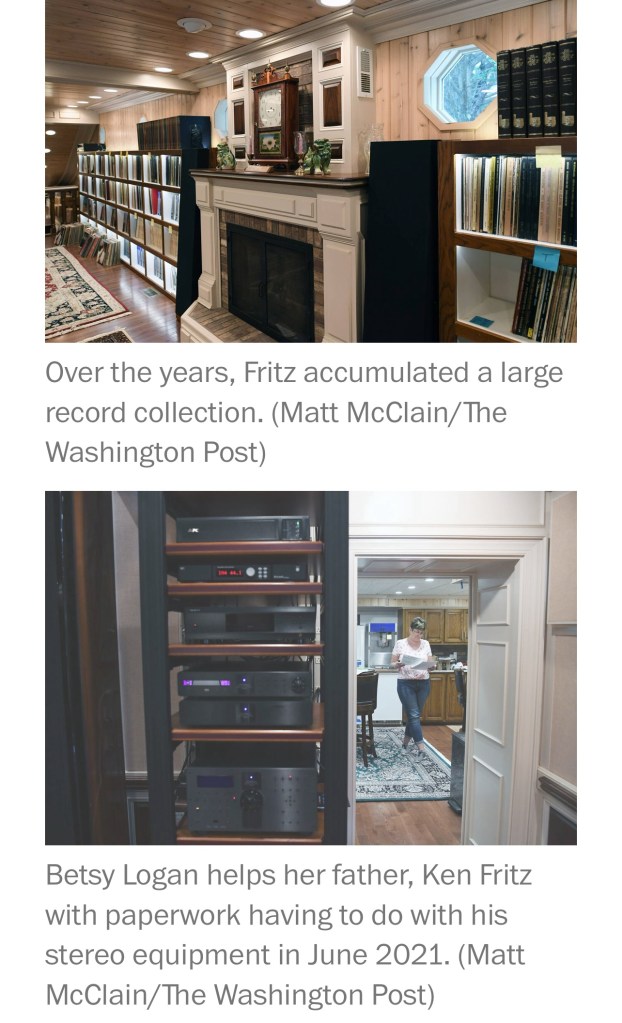

The faded photos tell the story of how the Fritz family helped him turn the living room of their modest split-level ranch on Hybla Road in Richmond’s North Chesterfield neighborhood into something of a concert hall — an environment precisely engineered for the one-of-a-kind acoustic majesty he craved. In one snapshot, his three daughters hold up newsiding for their expanding home. In another, his two boys pose next to the massive speaker shells. There’s the man of the house himself, a compact guy with slicked-back hair and a thin goatee, on the floor making adjustments to the system. He later estimated he spent $1 million on his mission, a number that did not begin to reflect the wear and tear on the household, the hidden costs of his children’s unpaid labor.

“My dad had a workshop,” is how Rosemary, the youngest girl, now 56, puts it. “We were forever building, rebuilding.”

But for the final flourish of his epic engineering project, in 2020, Fritz would go it alone.

He found just the right suction cups, four in total and the perfect size, from a company in Germany. He ordered a small vacuum pump online.

It would allow him to place a record on the turntable without even lifting the disc.

It was hardly the Frankentable’s most expensive enhancement, but it would fulfill a desire he could scarcely have imagined when he began his lifelong search for the perfect sound:

What’s the value of the world’s greatest stereo? Soon, everyone would know. But for now, just hit play.

Camille Saint-Saëns’s Symphony No. 3. It’s a favorite. Famous for its glorious pipe organ, it was the last symphony finished by the great French romantic composer.

“Should we listen, Dad?” asked Betsy, 59, the oldest of Fritz’s five children, and the only one up to help inventory his life’s work as his 80th birthday approached.

Fritz laughed.

“You won’t get a no from me,” he said.

The music builds slowly, lush strings answered by woodwinds, until the organ crashes into the mix and sparks a cascading piano dialogue that requires four hands. Its fullness and power washed over Fritz’s listening room.

He was a boy at the dawn of the hi-fi revolution. This was 70 years ago, long before holograms and virtual realities tried to fool our brains into seeing something that’s not there, when stereo first sold us an auditory experience like no other.

Just lower the needle, and an invisible 70-piece big band was transported into your living room — or a whispering crooner would come to life on the couch cushion beside you.

The trick, pioneered in the early 1930s by engineers working at Bell Labs in New York and Abbey Road Studios in London, was in the two channels of sound. Recorded from separate microphones and played back through separate speakers, they could simulate the swirling warmth and depth of life.

By the 1950s, the first bulky hi-fis were marketed for home use, blowing open the closed feel of the old phonographs — and offering a newly affluent nation a sophisticated new field of connoisseurship to conquer. The Mantovani Orchestraor Rosemary Clooney, pouring out of the Klipschorns with the after-dinner martinis.

One day, Fritz’s teacher at his Milwaukee grade school set up a turntable and speakers in the classroom. He was stunned by the beauty of the classical music. But he was especially thrilled by the sense of being on the cutting edge of a new technology.

Within a couple of years, teenage Fritz had bought his own recording machine and started capturing the music of live bands. He started the Hi-Fi Club at Bay View High School and took a part-time job in an appliance store that sold audio gear. With his earnings, he picked up a Heathkit, one of the hot, new build-it-yourself amplifiers, for $49.

You probably know a Ken Fritz. Maybe you are a bit of one yourself. Prosperous mid-century America produced a lot of Kens. The kind of people who gave their all to their hobbies — bowling, gardening, woodworking, stamp collecting — and refused to pay somebody else to manifest their dreams for them.

Like a lot of kids born to the children of the Depression, Fritz absorbed his DIY ethos from the previous generation. When their ’51 Chevrolet broke down, Ken Fritz Sr. didn’t have the money for a mechanic. So he took the engine apart himself and figured out how to install new piston rings. “He had never done that before,” Fritz recalled. “But he was smart enough to know how.”

At an audio show in 1957, Ken Jr. met Saul Marantz — an engineering legend in this burgeoning field, who a decade earlier had been so driven to convert an old car radio for home use that he took it apart and reconstructed it into a new invention, a preamplifier he dubbed the Audio Consolette. For a kid like Fritz, it was better than meeting Willie Mays.

“He looked like the guy on ‘Breaking Bad,’ just a little, but smaller,” Fritz recalled. “I told him I wanted to buy his amplifier. He knew I didn’t have the money.”

Fritz persuaded his boss at an audio shop to set Marantz up as a dealer. That earned him a discount, though he still had to work Saturdays to make up the rest.

After college, he worked for a business that made fiberglass molds and eventually moved to Virginia. He started his own company there, settling into the family home on Hybla Road in the mid-’70s.

He added a workshop and eventually built a swimming pool, something of a sop to his wife, Judy, and their kids, since he was too busy for travel or vacations. His company consumed the days. His audio obsession filled the nights and weekends.

In the 1980s, Fritz launched his project by blowing up the living room into a listening room, a 1,650-square-foot bump-out based on the same shoe box ratio, just under 2 to 1, that worked magic in concert halls from the Musikverein in Vienna to the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. The idea was that the acoustic waves would similarly roll off Fritz’s long, cement-filled walls and 17-foot-high, wood-paneled ceiling to bathe the listener in music.

He got his older son, Kurt, to help pour the concrete floors. Then he worked alongside a construction crew to put up the 12-inch-thick walls and the sound panels to line them.

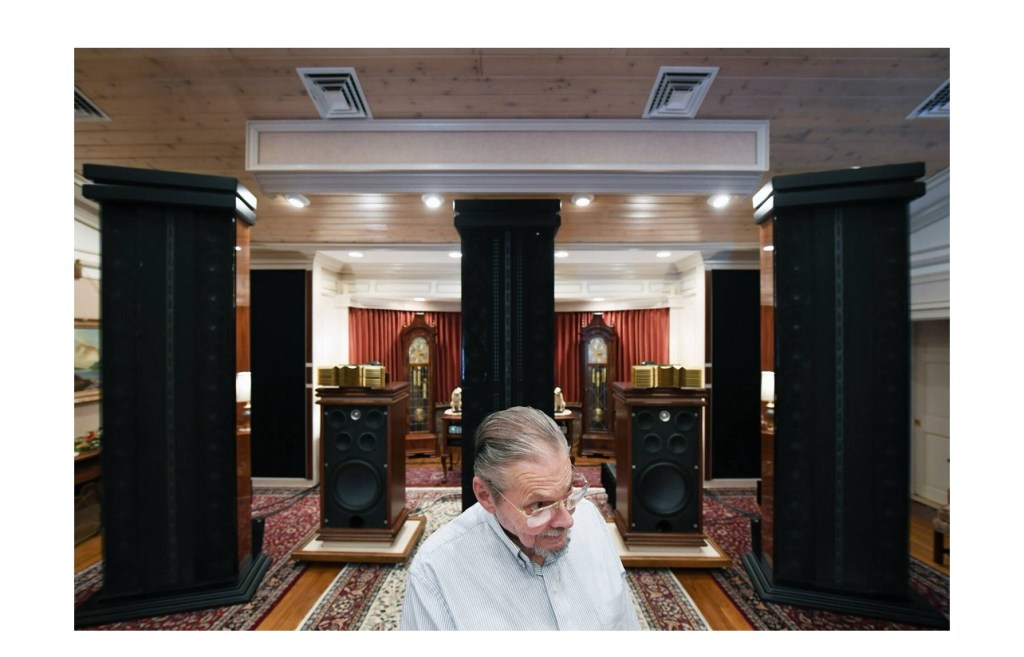

To minimize hum and potential electrical interference, Fritz outfitted the room with its own 200-amp electrical system and HVAC system, independent from the rest of the house.

He crafted by hand the three 10-foot speakers that loomed like alien monoliths at the head of the room, with the help of Paul Gibson, a former employee at his fiberglass company. Each 1,400-pound slab pulsed with 24 cone drivers for the deeper tones and 40 tweeters — 30 shooting into the room, 10 toward the crimson curtains draping the wall behind — to project the upper-range sounds.

He bought only a few of the components ready-made from a retailer. Fritz and his audiophile friends believed it was idiotic to invest in the kind of top-shelf equipment that gleamed from the glossy pages of High Fidelity magazine. Only a home-crafted system could achieve the audio you desired.

“You’re going to spend $250,000 for the name brand on the rack so everybody comes in and will be impressed,” scoffed Mark Mieckowski, a retired electrician who had helped Fritz fine-tune his system over the years. “DIY, there’s no name tags, nobody knows nothing. And I guarantee you those will probably sound a million times better.”

It was thrilling work. At night, Fritz would lie in bed and think about the progress he had made that day and the tasks that lay ahead for the next.

“I firmly believe that by the time a person, man or woman, is 19, 20, 21, they know what they’re going to do with their life,” he said. “And if you’re on that path and things are being done to your satisfaction, it’s easy to keep going to look for the next goal.”

Not everyone in the rapidly metastasizing house on Hybla Road shared this excitement.

In the faded photos taken as they worked alongside him, the five Fritz kids are offering pinched smiles, at best.

“Nobody wanted to come to our house, because he wanted to put them to work,” said his daughter Patty, 58. “I think we went camping twice, never took vacation. It was just work, work, work.”

Fritz thought he was teaching them about hard work and focus. A hard-driving boss at his company, he brought the same energy to his after-hours hobby, which he sometimes seemed to think of as everybody’s hobby.

He could be short. He held grudges. Devoted to sound, he often seemed not to listen.

Judy drank too much in those days. She also was unimpressed by her husband’s music. When he played “Swan Lake,” she’d call it “Pig Pond” in front of the kids and crank up the TV to annoy him.

After the divorce, she stopped drinking and found a longtime partner. Fritz moved on as well, finding happiness with Sue, who worked on making molds at his company; they married in 1995.

The biggest strain remained with older son Kurt, whom Fritz had once hoped would take over his business. But Kurt moved to New York for a job as a technology consultant. He needed the distance.

“Growing up, I had to get up at 6 in the morning to work,” Kurt, 55, said. “I basically was his slave.”

As he got older, Fritz sometimes wondered if he could have made space within his own vast ambitions to consider other people’s goals and wishes.

“I was a father pretty much in name,” Fritz told me. “I was not a typical father or a typical husband.”

The big blowup with Kurt came in 2018, about two years after Fritz had declared that, at last, the world’s greatest stereo and listening room was complete. Kurt, on a visit home, decided to ask his father for a couple of family heirlooms: his grandfather’s 1955 Chevy and an old Rek-O-Kut turntable.

It wasn’t the size of the ask. The record player wasn’t worth more than a few hundred dollars. But the tone of the demand set off Fritz. He heard in it a sense of entitlement.

“It could have been a monkey wrench, the way he told me,” Fritz recalled later. “I told him: ‘Not going to happen.’”

It was past 1 a.m. when Kurt, with a few drinks in him, told his father he was going to stay up later and listen to some more music. All the work he had put into building that stereo system — pouring concrete, painting the walls — now Kurt wanted to enjoy it.

But Fritz hit the off switch on the Krells. And Kurt delivered the words the two of them could never come back from.

“I need you to die slow, m—–f—–,” he told his father. “Die slow.”

His meaning was coldly clear to both of them.

Just a few months before, Fritz had noticed a weakness in his right hand. The diagnosis: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis — the progressive and inevitably fatal neurological disorder known as ALS.

That was it. Fritz called his attorney and disinherited Kurt.

His doctor had explained the cruel reality of Fritz’s disease. A small percentage of people go on to live years with ALS, continuing to work and function. But for most others, the transformation is rapid and devastating. People in the prime of life and health are robbed of muscular control and eventually the ability to speak, swallow and breathe.

For Fritz, there was initial hope, as he began treatment at Duke University Medical Center in North Carolina and continued to stay on his feet, that his case would progress slowly. But one day in 2020, he tried to use the Frankentable and found he couldn’t lift his arms.

“I can’t listen to these records anymore,” he told Sue.

“Well, if you want to sit down and tell me what you want to hear, I can put it on,” she replied.

But Fritz was not ready to relinquish control over his creation. That sparked the suction-cup idea. Fatal condition? Like all other hurdles on the path to the world’s greatest stereo, he would simply try to out-engineer it.

His plan was ingenious. It would involve rigging the suction cups to secure a record so he could shift it onto the turntable with a mere flip of a switch — a tiny gesture he felt confident his failing body would still allow for a while.

But before getting too deep into the project, he stopped. His neurological deterioration was accelerating. By the time he finished constructing the device, he realized, he wouldn’t even be able to remove a record from its sleeve.

A friend in Texas mailed Fritz a hard drive packed with thousands of songs, from Motown to Mozart. Now he could play music with his iPad. It might not have had the analog warmth of a Shaded Dog vinyl pressing of Arthur Rubinstein playing Beethoven, but on the Fritz system, through those mighty speakers, it wasn’t half-bad.

His younger son, Scott, 49, offered another welcome distraction.

They, too, had clashed over the years and occasionally stopped talking. Scott didn’t like how his father sometimes treated people. There was the time that Fritz blew up when a friend didn’t return some borrowed microphones promptly and insisted Scott go retrieve them, even though the man’s wife had just died. And Scott hatedhow his dad acted toward Kurt.

“He definitely taught me my work ethic,” Scott said. “But I don’t need to spend time with people who behave like that.”

Still, the two maintained a special bond, Scott having followed their shared passion into a career as a sound engineer in Chicago. In 2018, he and a filmmaker friend, Jeremy Bircher, drove to Virginia to make a documentary: “One Man’s Dream.”

The 58-minute film opens with Fritz, moodily backlit at his record shelves, grazing a hand across the jacket spines before landing on Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake.” In slow-motion close-ups, we see him press the disc to the turntable with a custom weight, lower the needle of an Air Tight PC-1 cartridge to the spinning grooves and carry a glass of wine to the paisley wing chair in the center of the Historic Williamsburg-meets-Victorian listening room. He faces those stalagmite speakers as the brass section collides with the swooning strings, taking it all in with a mesmerized smile.

Some audio professionals found it unbearable.

“You’re mining the lunatic fringe,” Jonathan Weiss, the owner of Brooklyn-based high-end audio boutique OMA, warned me when I told him about this story. Fritz, he argued, was the kind of obsessive who gives audiophiles a bad name.

But Steve Guttenberg, host of the popular Audiophiliac YouTube channel, shared the documentary with his 240,000 subscribers, calling Fritz “one of a kind.” It has now been viewed more than 1.9 million times on YouTube.

“This room/house must be listed in UNESCO World Heritage List. So much passion, soul and heart!” wrote one of the thousands of commenters.

“This is truly something that needs to be conserved,” wrote another, “as a memory to this inspiring man.”

One day in April 2021, Fritz hosted a small listening party. Before the pandemic, he frequently invited the entire Richmond Audio Society for sound and sandwiches. But on this day, it was just two of his closest audio-geek friends and me.

Ray Breakall, a professional piano tuner whose record collection is split between jazz and classical, remembered the first time Fritz played for him a 1950s recording of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with Fritz Reiner conducting.

“It was almost like the orchestra was in the room,” Breakall said. “That’s impossible if the room isn’t this size. Very scary and very realistic.”

Mieckowski — the sound buddy whose tastes ran more toward Five Finger Death Punch, a thrash-metal combo from Nevada, and who didn’t even own a turntable — was there, too.

“I can flat-out say this is the best system I’ve ever heard,” said Mieckowski. “Period.”

They talked more about the room, Fritz occasionally piping in but more often sitting back and listening, seemingly worn out. Betsy put out deli meat and rolls, and Fritz worked his way slowly through a sandwich, cutting up the pieces small enough to swallow. He seemed re-energized by the time they returned to the stereo.

“Here’s a great rock song, and it gets your juices going,” Fritz told us.

He punched up “Do You Love Me,” the 1962 hit featured so prominently in the musical melodrama “Dirty Dancing.”

And here it was, the inevitable moment in every meeting with an audiophile, when the proud owner of the system in question presses play.

I had experienced it when Weiss invited me to the OMA showroom to listen to the enormous horn speakers he sells for about $300,000 a pair; and when I sat in the cramped basement of veteran stereo-and-vinyl journalist Michael Fremer as he blasted the Beatles’ “Rubber Soul” through his Wilson speakers.

They all want to know: What do you think?

But as Fritz cranked the loudest version of the Contours hit I’d ever heard, it was impossible to listen critically. Was the bass flabby or tight? Did the mids sound right? What about the drums? The voice?

Fritz nodded, his eyes brightening. I found myself reflexively smiling, meeting his look with an expression of wonder, mouthing “wow.”

I was rooting for a man who had devoted his life to this system. I wanted it to sound better than any other. Even if I really couldn’t tell.

Was it truly “wow?” Or merely loud?

I noticed Mieckowski shake his head, involuntarily and almost imperceptibly, as soon as the music kicked in. He remained politely appreciative in front of his friend. But later, I followed him out to his car, where he confessed that, no, it sounded off that day.

He speculated that the Fritzes had probably been watching a DVD in the listening room and accidentally left the speakers on movie mode. A common mistake. But the fact that Fritz could no longer detect an imperfection in a system he had spent years honing to his impossibly high standards was a heartbreaking reminder of his friend’s physical decline.

“He can’t remember half the time what he’s listening to and what he’s left on,” Mieckowski said, referring to the system’s smorgasbord of settings.

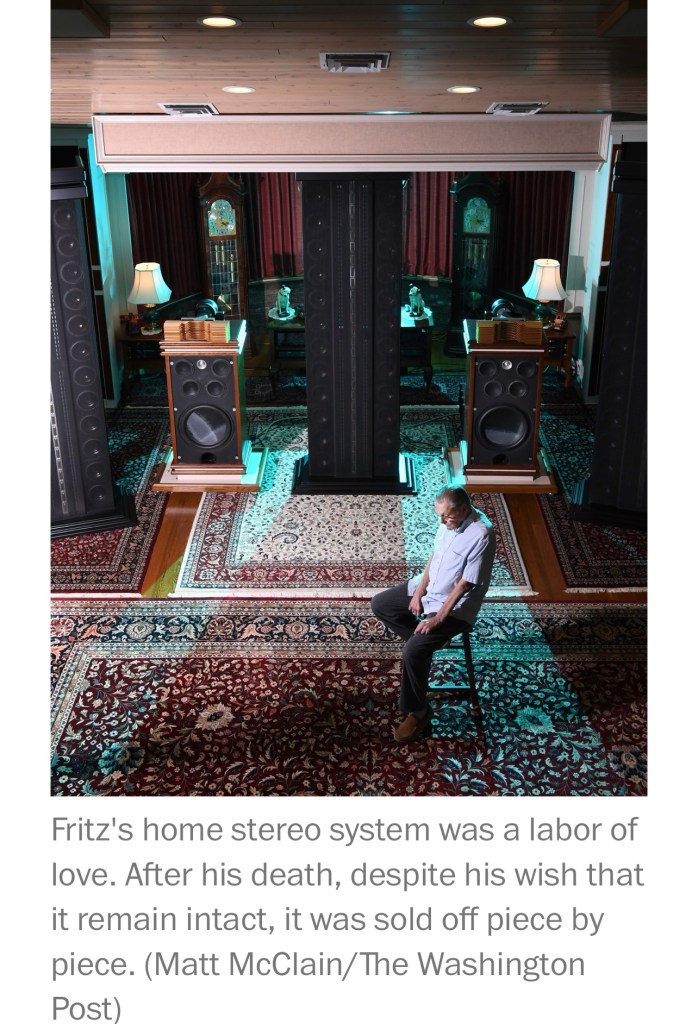

Three years earlier, in Scott’s documentary, Fritz had talked frankly about his condition, the limited number of years that remained for him and his hope that the world’s greatest stereo system would live on without him.

“I’d hate like heck to see this room parted out,” he had said. “That’s just like breaking up a dream.”

But on this night, Mieckowski had a glimpse of the not-so-distant future. Fritz’s stereo system may as well have been a load-bearing wall. His dream had been woven into the actual structure of his home. They were virtually inseparable.

And who would want to buy a stereo that cost more than the house?

“Anybody that’s got that kind of money,” Mieckowski said, “doesn’t want to live here.”

They gathered in the listening room one last time. Ken Fritz was turning 80. His sons weren’t there. Kurt remained estranged. Scott couldn’t make it down from Chicago. But Fritz’s three daughters and their husbands came and sang “Happy Birthday.” He sat for a portrait and even had a small spoon of ice cream, as much as his constricted throat muscles could tolerate.

It was February of 2022. Six years after he had finished his life’s project. Four years after he was told he only had so much longer to enjoy it.

Betsy, while helping him inventory his collection, had observed how her hard-charging dad had softened. He was able to share his regrets about his style of fathering. But he had no regrets about the hours, weeks and years that he had devoted to the world’s greatest stereo.

At some point, Betsy flicked the power on the 35,000-watt amplifiers and put on a selection of Christmas songs. Fritz always preferred his booming classical works, but the holiday tunes worked as background music, since they still had the 10-foot tree and the garlands on the banister. And Fritz wasn’t making a lot of musical choices anymore.

He was beyond the point where music could make him feel better, especially since he could no longer operate the system himself.

In April, around the time Betsy arranged to put a hospital bed on the ground floor so Fritz could avoid the stairs, she also tried to broker a peace.

Kurt called and tried to talk to his father. Betsy urged him to take the call. Fritz refused. In the end, they never spoke. On April 21, 2022, Fritz died.

And then it fell to Betsy to try to fulfill her father’s last, greatest wish.

For a time, it looked like an old audiophile pal of her father’s would buy both the house and the system. But he and his wife changed their minds.

Betsy talked to dealers about looking for other potential buyers. They were not enthusiastic.

Adam Wexler, with the Brooklyn-based StereoBuyers, told her he could resell the Krells. The custom-designed equipment would be a lot harder.

“Hi-fi is extremely subjective,” Wexler told me later. “So this guy built something that sounded good to him. How many people out there are going to say, ‘These are the speakers for me’ — and go through the hassle of acquiring these gigantic speakers that probably wouldn’t fit in most people’s homes, even if you could get them to their homes?”

Late last summer, Betsy realized she had to let go. Another couple wanted to buy the house — but not the stereo. She made a deal with a local online auction site, eBid Local, to catalogue and sell her father’s life’s work.

These people knew nothing about concert-hall acoustics, setting the vertical tracking angle or the magic of the perfect “Swan Lake” recording. They knew marketing.

“We euphemistically refer to it as the ‘million-dollar, monumental, magical, musical masterpiece,’” said David Staples, the owner of eBid Local. “It may be the best, most elaborate and exquisite private residential audiophile system in the country, perhaps even in the world.”

Many of the records her father had spent a lifetime collecting had already been sold — and Betsy understood that the system itself would almost certainly be parceled out to multiple buyers as well.

So what, ultimately, would be the value of the world’s greatest stereo?

The auction closed just before Thanksgiving.

The Frankentable? There were 44 bids, the top at a mere $19,750.

The 10-foot-tall speakers? After 18 bids, an Indiana man named Carlton Bale snagged all three for $10,100. Less than you’d pay for a pair of Yamaha NS-5000 bookshelf speakers.

A fan of Fritz’s YouTube documentary, Bale had set out a couple of years ago to build what he imagined would be “the second-best loudspeaker in the world” — until he heard about the Fritz auction.

“I thought, ‘Do I really have the time to build the speakers I want that probably aren’t going to sound as good as the ones Ken built?’” Bale recently recalled, after driving to Virginia with a U-Haul to fetch them last month. The price, he conceded, was “a steal. The bargain of a lifetime.”

The total take for the million-dollar stereo system, including the speakers, the turntable, the dozens of other components from detached cones to the reel-to-reel decks? $156,800.

But perhaps that was always going to be its fate. Last summer, when pressed about the value of Ken Fritz’s life’s work, Staples had demurred.

The value, the auctioneer said, was whatever somebody else was willing to pay for it.

About this story

Design and development by Brandon Ferrill. Design editing by Eddie Alvarez. Photo editing by Moira Haney. Video by Allie Caren. Senior video producing by Nicki DeMarco. Audio production by Bishop Sand. Story editing by Amy Argetsinger. Additional editing by Phil Lueck and Christopher Rickett. Additional support by Maddie Driggers.

Geoff Edgers, The Washington Post’s national arts reporter, covers everything from fine arts to popular culture. He’s the author of “Walk This Way: Run-DMC, Aerosmith, and the Song That Changed American Music Forever.”

.png)