(I was so happy to read this article in The New York Times. This is where we went with clients over the years when we wanted to feel like big shots. We sat next to DeNiro, Rushdie, Wintour, and Karan. It was thrilling). —LWH

For decades, Silvano Marchetto’s Greenwich Village trattoria was a celebrity haven, serving Brad Pitt, Beyoncé and Jay-Z. Then he vanished. What happened?

By Alex Vadukul

Alex Vadukul reported this story from Florence, Italy.

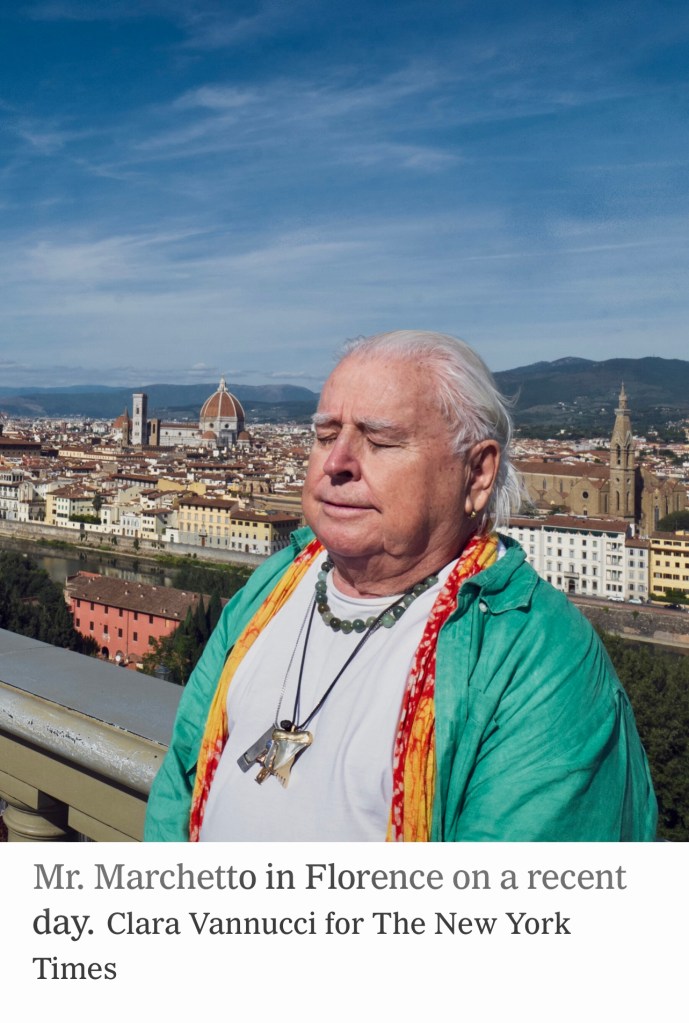

One recent morning, in the bustle of Florence’s ancient central market, Silvano Marchetto, a stout 76-year-old man with a mane of white hair, sat nursing a Negroni as he considered what he wanted to cook for dinner. The butchers and fishmongers who walked by threw respectful nods his way.

The silver bracelets on his wrists jangled as he polished off his drink. Shuffling past meat displays and fruit stands as he went deeper into the market, he grunted reminiscences about his old life in New York City, back when he ran a celebrity haven in Greenwich Village, Da Silvano.

“Lou Reed always said I served the best branzino.”

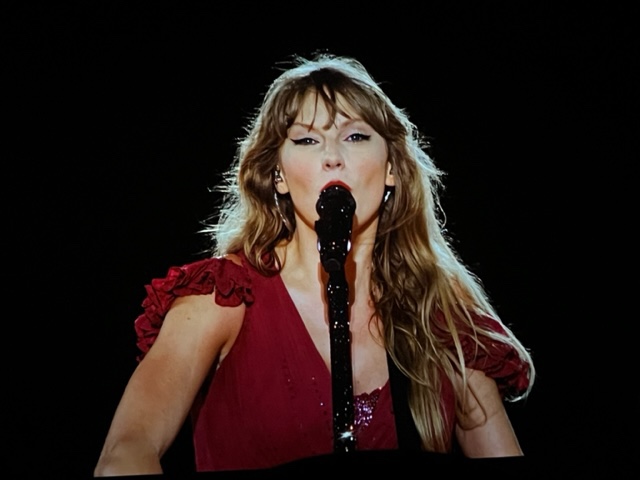

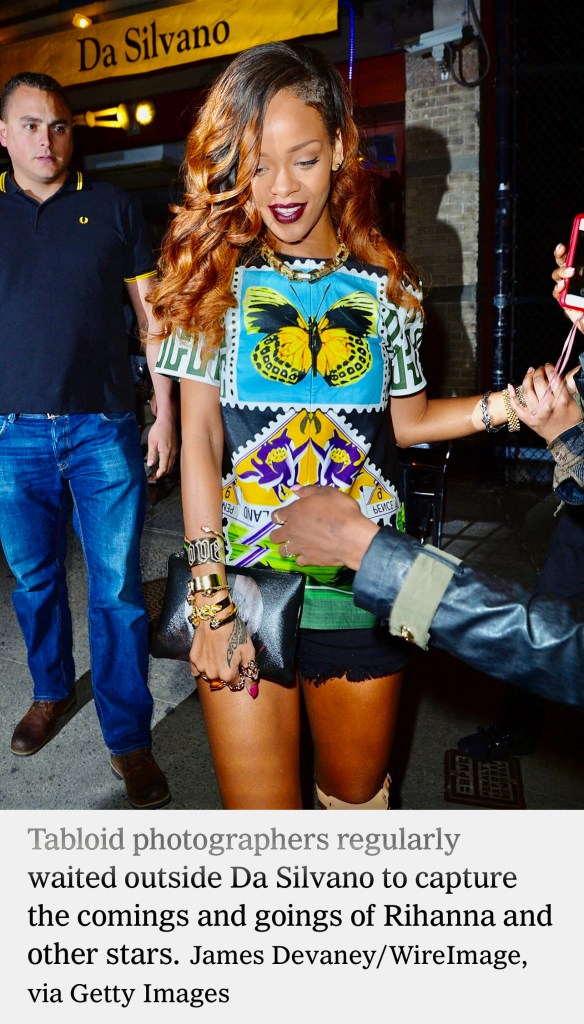

“Rihanna loved my taglierini contadina.”

“Anna Wintour’s ex-husband used to love my rabbit.”

Mr. Marchetto liked the look of some fresh porcini, so he resolved to cook monkfish with mushrooms. His next stop was a vegetable stall. Its operator, Elena Popa, gave him a look.

“Are you famous or something?” she asked in Italian.

“I ran a restaurant in New York called Da Silvano,” he said. “Closed now.”

“Why?”

“Because. The rent. My knees. Divorce.”

“If it was successful, couldn’t someone have just kept running it for you?” she asked.

“Someone else run Da Silvano?” he said. “Absolutely not!”

In certain New York circles, Da Silvano needs no introduction, and neither does Mr. Marchetto, who for four decades ran his trattoria as one of the city’s reigning downtown canteens for the art, fashion, film and media crowds.

That reign ended when he closed Da Silvano with little warning in 2016. Then Mr. Marchetto vanished from public view.

This summer, when I started making calls in an effort to track him down, some of the tips I heard were outlandish: He was on the run in the South of France; he’d opened a beach pizzeria in Cyprus; he was operating a tiny, one-man trattoria in rural Italy; a Vogue photographer I spoke with had heard he was dead; and the designer Isaac Mizrahi, a onetime regular, said he had “no idea what happened to him.”

“Da Silvano now represents a lost era of downtown New York, and he was its rustic host,” Mr. Mizrahi said. “I’m still mourning it, and I still glance at its old address whenever I go up Sixth Avenue and think, ‘Where did he go?’”

Mr. Marchetto opened the restaurant in 1975 with the idea of serving New Yorkers the rustic cuisine he had grown up with in Tuscany. Italian fine dining in the city was then typified by spaghetti and meatballs served with Chianti from straw-covered bottles, so his preparations of liver crostini and tripe stew proved revelatory.

“I was just cooking what I knew to cook,” he said as he drove from the market back to his villa in the Tuscan hills. “Early on, I even served birds off-menu. I bought robins at a pet shop on Thompson Streetand served them roasted with bacon.”

The art dealers Leo Castelli and Mary Boone were starting their galleries in SoHo around the same time that Da Silvano opened, and they soon made it their hangout. “Castelli used to go crazy for my polenta,” Mr. Marchetto said. Gradually, the patio tables beneath the yellow awning became prime seating for those who wanted to be seen. Paparazzi posted up to document Sarah Jessica Parker eating steamed artichokes and Jay-Z and Beyoncé on one of their first public dates.

The crowd came to include Calvin Klein, Yoko Ono, Lindsay Lohan, Joan Didion, Harvey Weinstein, Madonna, Salman Rushdie, Uma Thurman, Stephanie Seymour, Susan Sontag, Graydon Carter and Larry Gagosian. While Gwyneth Paltrow and Brad Pitt were engaged in 1997, they left notes in Da Silvano’s guest book: “Thank you for letting us smoke,” she wrote. “And smoke and smoke,” he added.

Da Silvano also provided endless fodder for The New York Post, which covered the trattoria as if it were the White House. A typical 2013 itemfrom its Page Six column reported that the art dealer Tony Shafrazi shouted at Peter Brant and Owen Wilson, while Wilson ate a dandelion and heirloom tomato salad, because they hadn’t been returning his calls. In 2014, while Rose McGowan was having a meal, a man emergedfrom a subway grate and tossed a smoke bomb at Bar Pitti, the Italian restaurant next door. The tabloid speculated that the incident was connected to the feudbetween the trattorias.

“Page Six covered us so much people asked if I owned The New York Post,” Mr. Marchetto said. “But it was good for Da Silvano, whatever they wrote.”

Mr. Marchetto became a downtown celebrity in his own right, and a cartoon logo of him wearing sunglasses was branded onto Da Silvano’s espresso cups and olive oil bottles.

He lived a block away with his wife, Marisa Acocella, a New Yorker cartoonist and graphic novelist, and he went home for midday naps. He parked his Ferraris ornamentally outside the restaurant. He wore scarves, yellow pants and Hawaiian shirts. He hired young Italian waiters who flirted with the models and actresses.

But as blogs and social media began to rival Page Six as a source of celebrity gossip, his restaurant lost some of its luster. And as smartphones ushered in an era in which a celebrity’s nightlife indiscretions could be documented, the machismo-fueled party at Da Silvano began to look a little dated. In 2013, a rival Italian restaurant, Carbone, opened nearby to praise from critics, who welcomed the swing back to red-sauce recipes, and became a haunt for Drake, Jennifer Lopez and multiple Kardashians.

Around the same time, Mr. Marchetto’s life turned tumultuous. A manager at his garage filed a sexual harassment suit, claiming that Mr. Marchetto had grabbed his genitals after dropping off one of his Ferraris; waiters filed a class-action lawsuit, claiming that he had withheld wages. Mr. Marchetto denied the allegations, and both caseswere settled out of court. In 2016, after 12 years of marriage, his wife filed for divorce, leading to a contentious trial.

Mr. Marchetto abruptly closed Da Silvano on the night of Dec. 20, 2016. His explanation was straightforward: The rent had spiked to $42,500 a month. “A fortune, I couldn’t handle it,” he told The New York Times that week. “Everybody is sad; it’s been 41 years and 51 days exactly since I opened, but I don’t care.”

Celebrities mourned its closing. A few stayed in touch.

“I visited him in Florence because I was playing a show, and he was living outside the city with his olive trees,” Patti Smith said. “I think Silvano’s heart was broken when he had to close his restaurant, so he needed to leave New York. When I saw him, he looked like he was finding happiness out there.”

When I finally reached Mr. Marchetto in Italy by phone, he hastily explained that he hadn’t received my numerous messages because he does “not really check email,” and instructed me to meet him outside Florence’s train station in three days.

That afternoon, he drove me to a hilltop hotel, Villa San Michele. A doorman, Paolo Greco, greeted Mr. Marchetto and announced him to a young hostess, saying: “Do you know who this is? He’s a myth. Back in New York, he knew them all: the angels and the scoundrels.”

In the courtyard, Mr. Marchetto savored a vermentino and described his life now: “I let the days go by. I have a drink for lunch. I go home and nap. Then I go out again. I’ll sit in a piazza for hours. I grow figs and bottle olive oil from my trees.”

Do you look back?

“Once in a blue moon. I miss the action, but I never feel sorry for myself.”

Any gossip?

“Donald Trump came in once. Wanted spaghetti and meatballs. I said, ‘We don’t do that here.’ He said, ‘But that’s what I eat.’ So we made it for him.”

Do you remember your last night of service?

“I bought two kilos of caviar and handed it to people,” he said. “I told them, ‘Tonight is our last evening.’ They looked at me like I was joking, but I was crying inside.”

Coldplay blared as we drove to his hillside villa near Bagno a Ripoli. While he took a nap, I perused the relics of his old life: a framed letter from Barack and Michelle Obama wishing him a happy 70th birthday; some Da Silvano business cards; a portrait of him from the 1970s in Greenwich Village in which he has flowing dark hair and is riding a Honda motorcycle.

That evening, at a restaurant on a lonely piazza, he was joined by an old friend, Aldo Antonacci. Over Sangiovese, they reminisced about how heads would turn when Monica Bellucci walked into Da Silvano, and Mr. Antonacci said he still dreamed about the fiori di zucca.

For dessert, Mr. Marchetto ordered Gorgonzola. Then he leaned forward to tell Mr. Antonacci: “Did you hear about my restaurant in Cyprus? It was un casino.”

The Italian term un casinomeans a disaster.

The precise details of the recent reboot of Da Silvano on the island of Cyprus are somewhat opaque, because the restaurant is now closed and its existence was barely publicized. But for a moment Mr. Marchetto got back into the game this summer, opening a beachy version of his trattoria in Ayia Napa, a resort town known for its nightlife.

For four months, Da Silvano Cyprus served British and Swedish tourists and young women who stopped in for Instagram selfies before going clubbing. The cartoon logo of Mr. Marchetto appeared in a sign above the entrance and was branded onto menus and place mats. The restaurant offered Da Silvano hits like spaghetti puttanesca.

According to Mr. Marchetto, the restaurant came into being after a longtime former Da Silvano regular, Stephen Conte, a radiologist from New Jersey who vacations in Cyprus, pitched him the idea.

“He said he could make me good money if I lent my name, so I figured why not,” Mr. Marchetto said. “So I went to Cyprus to teach them how to make osso buco and my signature pastas. I noticed problems, like it was hard finding good ingredients and cooks, but I was just excited to get back into a restaurant.”

By midsummer, Da Silvano Cyprus was struggling. There were kitchen staffing troubles, and the restaurant started selling mostly pizza.

“We tried doing something this summer, it didn’t work out, but it was an honor working alongside Silvano,” Mr. Conte said. “I plan to try opening again next season.”

“It’s not easy running a restaurant,” Mr. Marchetto said. “The experience reminded me I should follow what I’m good at more. If someone asked me to open a place tomorrow, now I probably would.”

After the next day’s afternoon nap, Mr. Marchetto poured himself a Montepulciano and started preparing the monkfish with porcini. As the glow of a sunset crept into his villa, he chopped the mushrooms and skinned the fish, setting aside its head for a stew. He swatted away a fly as he tossed the porcini into a sizzling pan filled with the monkfish fillets, grape tomatoes and shallots.

As we ate at his kitchen counter, he took out his phone and pulled up a video posted to Da Silvano’s Facebook page in 2013. It showed Rihanna, wearing sunglasses and a baseball cap during a busy night at the restaurant.

“Hello Mr. Silvano, it’s your favorite customer, Rihanna, wishing you a happy 38th anniversary,” she said. “You’ve been here since 1975. That’s a big deal to be here in New York City at the same spot. This place is legendary. I love coming here. And I will always come here as long as you are here.”

He smiled as the clip finished. Then he poured himself another glass of wine and stepped outside to take in the silence of the Tuscan night.

Alex Vadukul is a city correspondent for The New York Times. He writes for Styles and is a three-time winner of the New York Press Club award for city writing and a three-time winner of Silurians Press Club medallions for his feature writing. He was a longtime writer for Sunday Metropolitan and has been a reporter on the Obituaries desk.More about Alex Vadukul