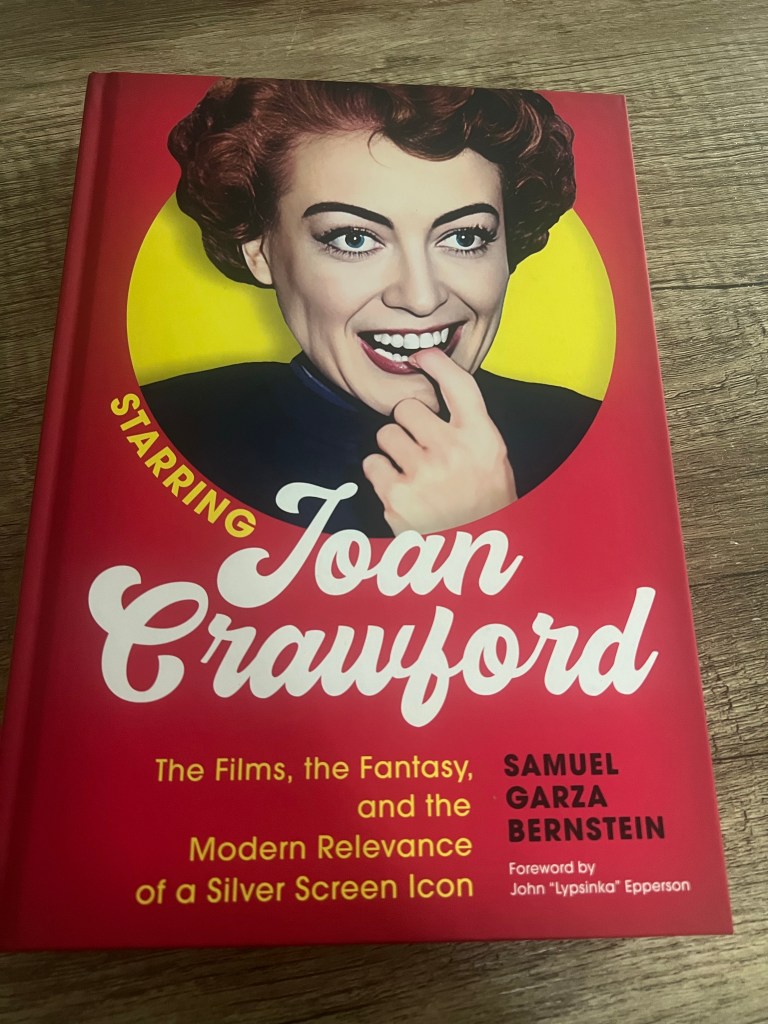

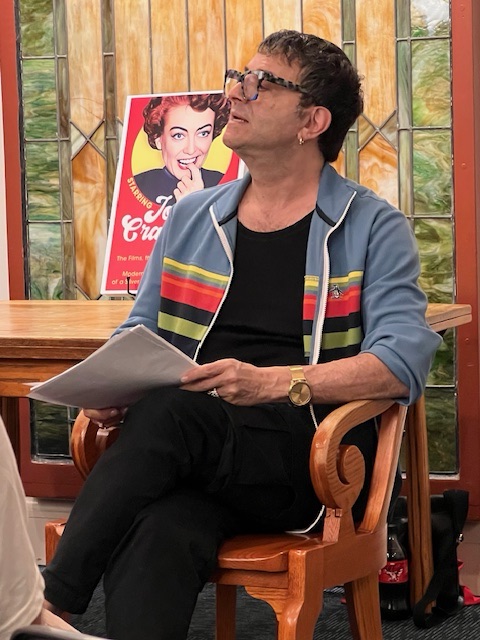

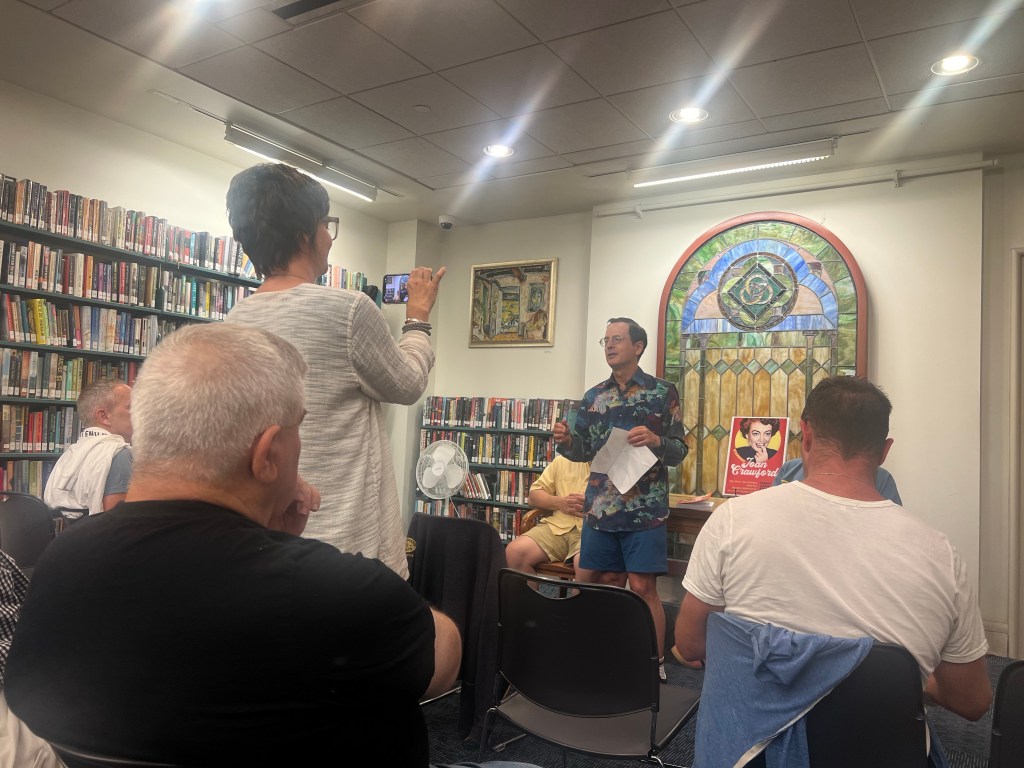

East End Books Ptown put on quite a performance last night at the Provincetown Public Library by featuring Sam Bernstein and his Joan Crawford book. Oh, the stuff we learned. Sam was so entertaining that the audience stayed well beyond the designated time. Can’t wait to read the book. Thank you Jeff G. Peters.

————————————————

“It’s one of the only places in the world where unconventional people are not just tolerated, but preferred.” The words of Michael Cunningham, an American novelist and screenwriter.

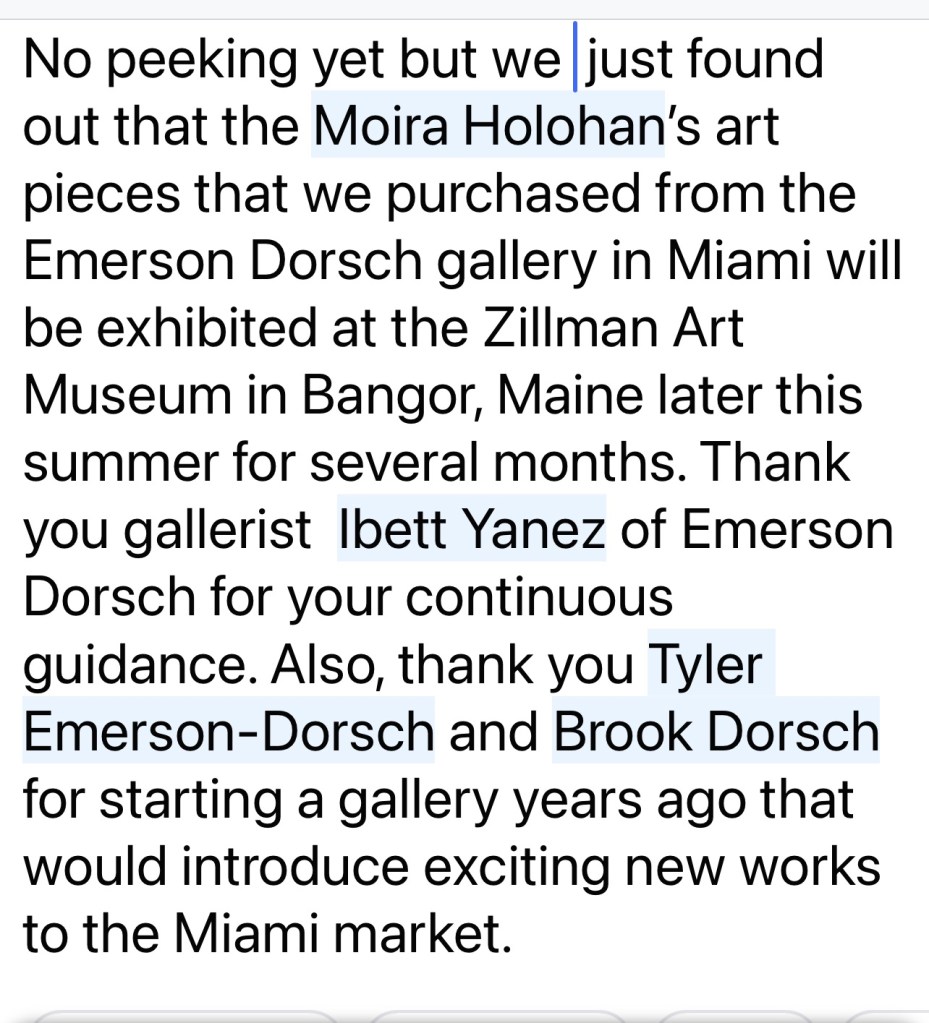

He wrote the introduction to the “Artists of Provincetown,” a book and exhibit at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, PAMM. We were at PAMM yesterday.

Cunningham says, “When anyone asks me why I’m so attached to Provincetown I generally say something along the lines of, “It’s one of the only places in the world where unconventional people are not just tolerated, but preferred.”

I’m not happy about the fact that the world at large considers artists, writers, musicians and others anyone who creates something out of nothing to be “unconventional.” I’d prefer a world in which people who harbor no urge to create are the unconventional ones.

We do, however, live in this world. In this world, people who create can, for the most part, only be reconsidered for the title conventional if they and their work become famous. The urge to create, and the stunningly hard work it requires, doesn’t always mean much. Success means a great deal. In a city like New York, people who are initially interested in the fact that you’re an artist or a writer or a musician tend to become less interested if they learn that you aren’t yet represented by a gallery, have yet to publish anything, have not yet released a hit song.

And so we, whether we live full time or part time in Provincetown, have collectively established a world within the larger world a place where creators are not only honored and respected for their efforts, but are honored and respected whether or not they’ve become famous. They are, in fact, honored and respected if they never become famous.

Provincetown knows, in ways many other places don’t, that significant work doesn’t always = widespread recognition.

This understanding has been shared among us for well over a hundred years. We who live in Provincetown now are the great-great-grandchildren of Hans Hofmann, who might have been speaking about Provincetown itself when he said that his aim in painting was to create pulsing, luminous, and open surfaces that emanate a mystic light.

We are, as well, the great-great-grandchildren of Eugene O’Neil and Susan Glaspell whose plays, in the 1920s, were equally locally renowned. It doesn’t matter, not really, that only one of them went on to be inducted into the literary canon.

Both were lauded for their work as they were creating their work.

It helps that Provincetown’s moody beauty, and its relative isolation, imply the making of art more powerfully than do many other places. How else, exactly, are we to respond to blinding blue autumn skies arcing over the glittering blue-black Atlantic, or to misty spring afternoons when the lilacs seem to have blossomed overnight those interludes during which Provincetown all but whispers, you have no other home than this.

We are not, of course, compelled to depict Provincetown directly. But any response to Provincetown and its surroundings other than elation can feel more than a little miserly. At certain hours, on certain days, it’s easy to feel as if there are only two possible responses: fall to our knees, or do whatever we can to pay it homage in other, more corporeal ways. Or both.

Making art, like those beatific days in Provincetown, can be transcendent. I feel reasonably sure that all the artists pictured here have had their share of good and great days—the days when it pours out, when it’s coming through you as well as from you, when you know with absolute certainty that you’re using your gifts to their outermost limits. The days when the work itself whispers, you have no other home than this.

On the other hand, art has a way of turning off the tap, sometimes as suddenly and unexpectedly as it turned the tap on. Making art can, with surprising swiftness, turn from an ecstatic outpouring of our love, our rage, our pure astonishment at life itself into an effort that more nearly resembles pushing a piano up a flight of stairs.

Provincetown, too, can be as difficult as it is rapturous. Its challenges range from hurricanes and floods to ever-more-astronomical rents. Living in Provincetown now is only slightly less expensive than living in San Francisco, or Tokyo. I’m not sure how artists, unless they have trust funds, can move to Provincetown today. I’m not sure, for that matter, how artists who’ve been here for decades are able to remain, if they’re able to remain at all.

Along with Provincetown’s catastrophic expense, Commercial Street in the summers is as crowded as a subway at rush hour. The artistic impulse can wither a bit in the face of all those tourists, all those souvenirs and t-shirts. In winters, it’s possible to walk down Commercial Street, past the boarded-up shops and restaurants, without seeing a single other person. There are almost no year-round jobs.

Provincetown is remote, not just literally but in the worldly sense, as well. If you live here it’s easy to imagine, for better and for worse, that there’s no other world but Provincetown.

I should add that, for some of us, those are virtues, not liabilities.

Still. As far as I know, at least nine of out ten of the artists portrayed in this book have made significant efforts not only to get here but to stay here.

Most work, of any kind, isn’t easy, from performing surgery to mixing drinks behind a bar. I wouldn’t want to over-romanticize those who create. I can, however, say with confidence that many of the people portrayed here have, along with the good days, survived periods of deep loneliness, crippling doubt, and a periodic sense of futility that tends to strike us not as a fallow period but as truth, revealed. How could we have failed to realize that we can’t really do this at all? Not to mention the desire to produce something too great for any living being to produce, which can miniaturize our own attempts.

Producing art, like living in Provincetown, requires a degree of daily determination, in the face of the doubts and the foods; in the face of landlords who, without notice, double our rent.

There are, in short, many sensible reasons not to live in Provincetown, just as there are many sensible reasons not to create. It’s always a gamble, for everyone. Will it be a hit, or a miss, not only for others but for you, yourself?

And how much longer can we put off paying the electric bill before they turn our power off? As occupations go, being an artist is one of the least reasonable of all possibilities.

And yet, everyone portrayed in this book has insisted on remaining unreasonable. For me, a working definition of an artist is someone who persists not only in creating art but in living, as best we can, with an ideal that remains, despite our every effort, slightly out of reach.

The artists in these portraits, then, are not only accomplished, but are survivors. Victorious survivors.

Full disclosure: I’m in the book, too.

All gratitude to Ron Amato and Pasquale Natale for bringing this book to fruition. The book is important now, and it’ll be important in the future, as a record of those who found their way to a town on a remote spit of sand and produced work that will endure, even after its creators are gone. For all of our differences, everyone in this book is engaged in the same effort.

Everyone in this book has, by dint of hard work and the summoning of magic, produced something that the world requires, if it is to survive at all.