The Miami art world is getting a jolt of New York energy. There is a new collaboration between Pendentive Studio and Kates-Ferri Projects that will bring artists represented by the New York City gallery to Miami audiences.

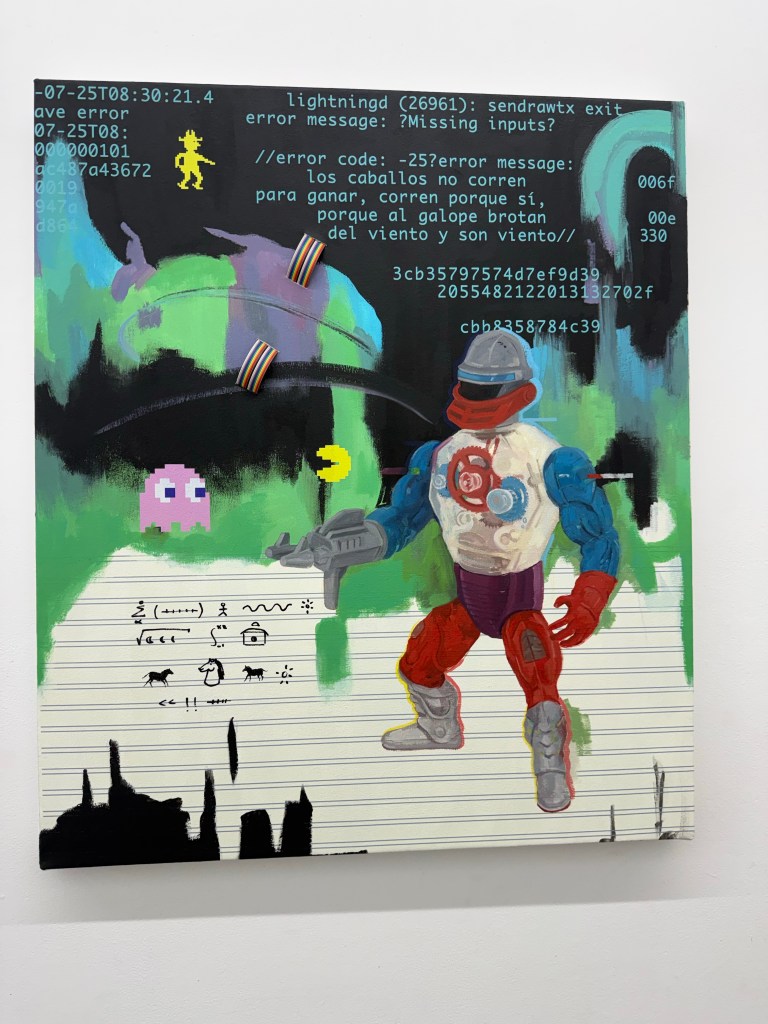

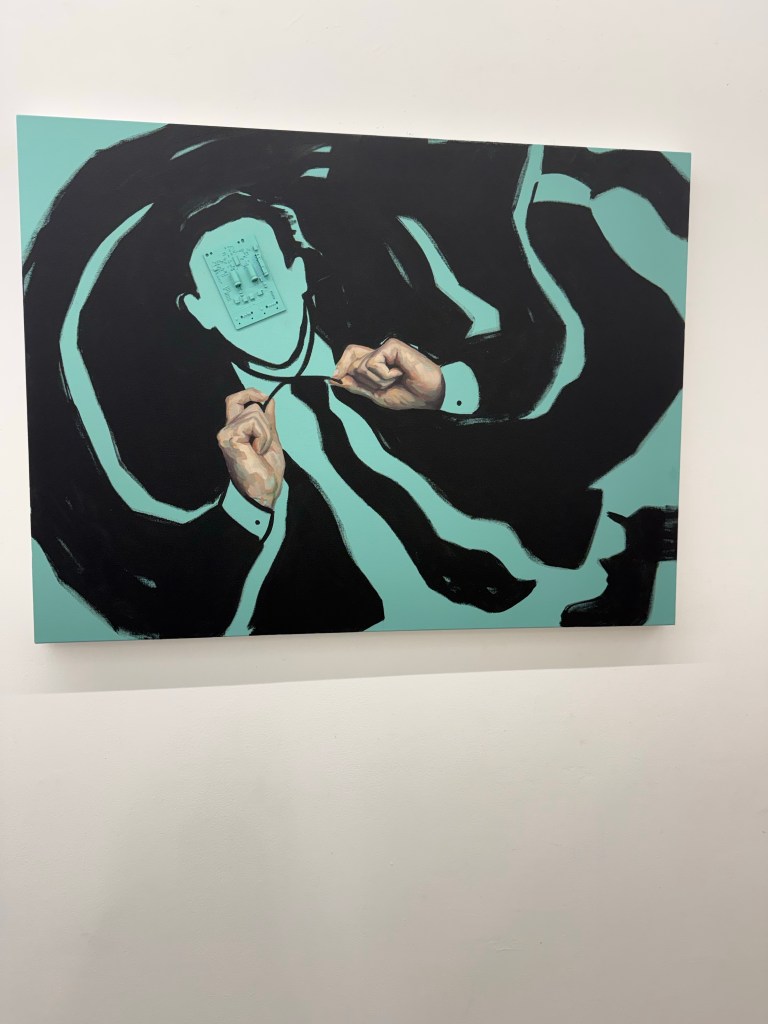

The partnership kicks off Friday, March 13th with a group exhibition at Pendentive Studio (7615 Biscayne Blvd) featuring Lisu Vega and Juan Henriquez. Interior designer Phoebe O’Neill owns Pendentive Studio.

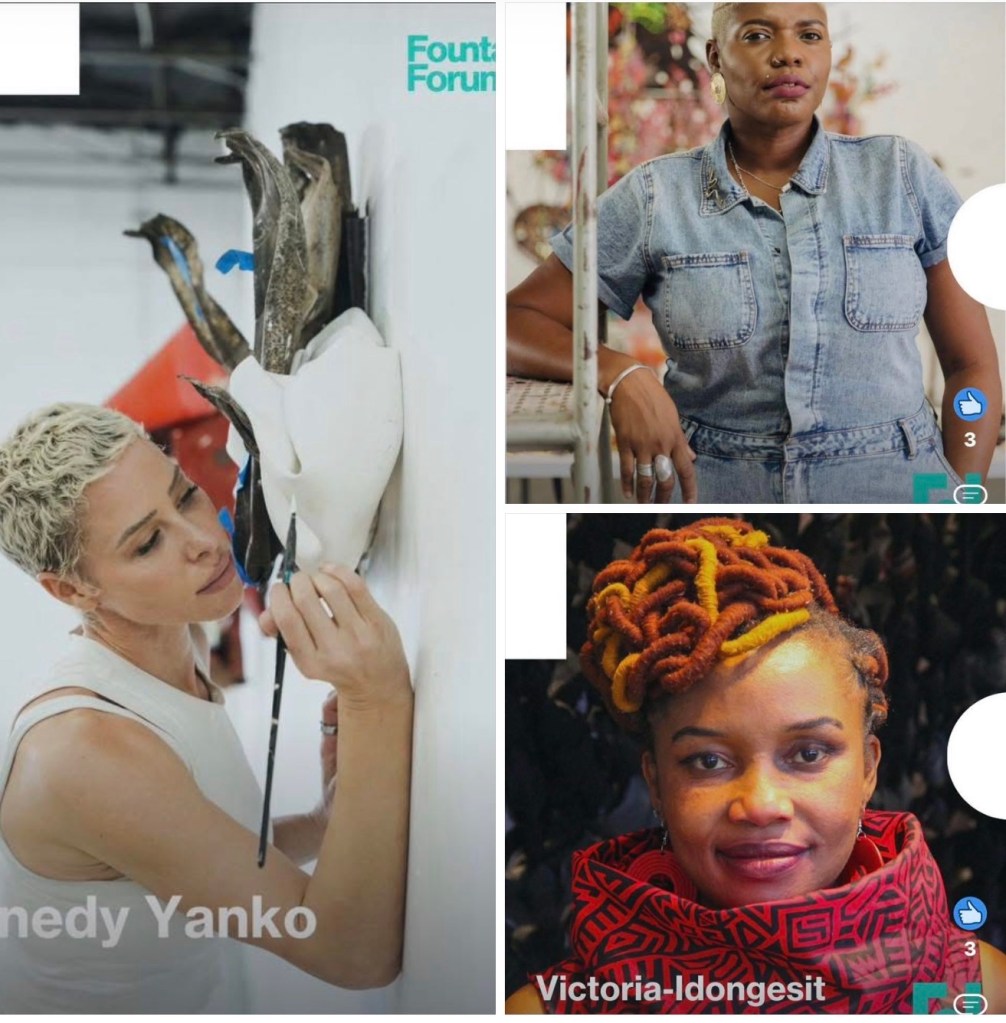

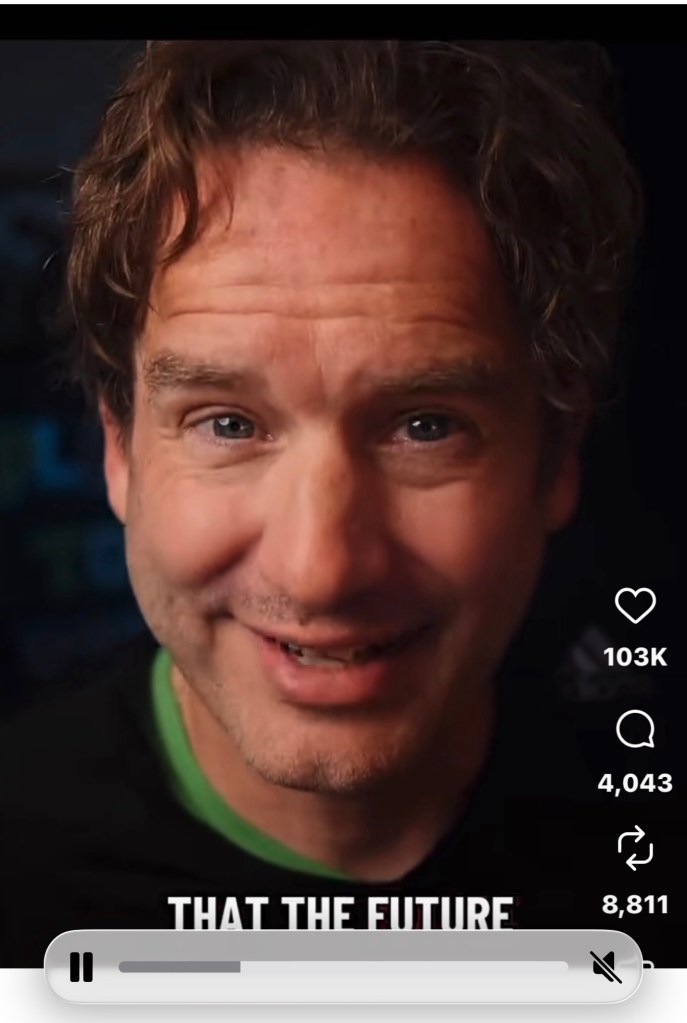

The 56th episode of Art Lovers Forum was very fortunate to secure an interview with Natalie Kates so we can hear how this partnership will work and learn more about Natalie and the gallery she created on the lower east side of Manhattan with her husband Professor Fabrizio Ferri.

Natalie is one of the most passionate gallerists I have ever spoken to. She has a spirit that allows her to move forward in a remarkable independent fashion. When Natalie believes in something she makes it work. She evaluates success by discovering, nurturing, and promoting emerging artists.

That’s why she is very excited about displaying artwork in Miami. Natalie wants to explore and experiment with exhibiting artwork in a room filled with highly designed furniture and accessories. “It will be interesting to see the reaction of collectors when they walk into a room that is not white and empty. We just may be onto something.”

Listen to episode 56 of the Art Lovers Forum podcast here –https://www.artloversforum.com/e/episode-56-natalie-kates/

The Art Lovers Forum Podcast is also available on popular podcast sites, including:

Apple Podcasts –https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/art-lovers-forum-podcast/id1725034621

Spotify –https://open.spotify.com/show/5FkkeWv83Hs4ADm13ctTZi

Amazon Music –https://music.amazon.com/podcasts/77484212-60c5-4026-a96f-bd2d4ae955c6

Audible – https://www.audible.com/pd/Art-Lovers-Forum-Podcast-Podcast/B0CRR1XYLZ

iHeartRadio –https://www.iheart.com/podcast/1323-art-lovers-forum-podcast-141592278/

Contact:

Lois Whitman-Hess