.

Monthly Archives: April 2025

A Full-Body MRI Scan Could Save Your Life. Or Ruin It

(A friend of mine swears by the full-body MRI Scan. He urges people to get it. Here are some other thoughts about whole body MRI’s. —LWH)

BY Matt Fuchs

Calvin Sun was a healthy 37-year-old when a full-body MRI scan showed a cyst in his kidney. Sun saw a urologist who was cautiously optimistic that it wasn’t cancerous and offered him a surgery appointment several weeks away to inspect the kidney and operate if necessary. “I was like, how about tomorrow?” Sun recalls.

As an ER doctor, Sun is used to decisive problem-solving. It’s the “right mindset” for undergoing a whole-body MRI, he says. “You have to be willing to take 100% responsibility for the consequences, good and bad.”

Instead of traditional scans, like CTs or MRIs of a specific part of the body, full-body MRI scans require just an hour to image you from head-to-toe. Celebrities and influencers are holding them up as a pillar of preventive health to catch problems early on, wherever they’re hiding—before they become hard-to-treat diseases. Dwyane Wade, for example, recently credited a whole-body MRI with alerting him to an early-stage kidney cancer.

However, most medical experts are more wary. “The odds that you’re going to be hurt are higher than the odds you’re going to be helped,” says Dr. Matthew Davenport, professor of urology and radiology at the University of Michigan.

Here’s what to know about this relatively new technology—both its promise and shortcomings.

What is a full-body MRI scan?

First offered in the early 2000s, a whole-body MRI is like looking at a city from a distance, says Dr. Heide Daldrup-Link, professor of pediatric oncology at Stanford. “You might always find a high-rise building, but you won’t find a spider,” she says.

With this panoramic view of the body, doctors may spot big problems, like a large tumor. “But we can very easily miss small tumors” without scans that zoom in, Daldrup-Link explains. CTs or organ-specific MRIs are needed to fully investigate health issues like cancer and most brain abnormalities, she says.

An advantage of whole-body MRIs over CTs is that they use magnets and radio waves, which eliminate the type of radiation linked to cancer. But that doesn’t mean they’re risk-free or the right choice for everyone, Davenport says.

Who benefits?

For nine years, Dr. Dan Durand oversaw an outcomes-focused health care network in Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods. Some people are incredulous, he says, that he’s now the chief medical officer at Prenuvo, a company specializing in whole-body MRIs starting at $2,500 a pop (and not covered by insurance for the average, symptom-free person).

But Durand and others view whole-body MRIs as key to the future of health for everybody, not just rich bodies. “We’ll look back on whole-body MRIs the same way as your cell phone or computer,” he says.

They’re already beginning to change health care, he says, by detecting “silent killers lurking,” like aneurysms or cancers. “We can find Stage I cancers before symptoms appear,” he says. The technology is advancing, becoming faster and more accurate.

Daldrup-Link agrees that whole-body MRIs can “detect diseases in early stages.” Dwyane Wade’s case “may underscore the potential benefits of early cancer detection.” But the patients who benefit most have unique risks, such as people born with certain genetic syndromes that cause random cancers throughout the body. “Whole-body scans are really helpful” to identify these cancers, she says.

Such syndromes are relatively rare, though Daldrup-Link gives about two whole-body scans per week and sees a wide variety of cancer predispositions like Li Fraumeni syndrome and retinoblastoma.

Full-body MRIs provide information about some other conditions besides cancer and brain pathologies, she notes, like certain skin and muscle infections, and disorders involving abnormal blood vessels.

People with such known conditions or risks get “even more value” from the images, Durand says, but this type of MRI can raise awareness about anyone’s state of health, he adds. His own scan picked up on joint inflammation and damage, which he’s now treating to keep in check.

They can also show excess visceral fat before heart disease and other chronic illnesses develop. Such findings provide benchmarks for tracking how interventions are working. Prenuvo recommends adults under age 40 get scans once every two years if their first scan didn’t show a problem. If you’re older or your first scan did find an issue, the company advises scans yearly or even more often. However, these are just the company’s recommendations; major medical groups do not currently recommend whole-body MRIs for the general population.

The drawbacks

If you have no symptoms or unique risks, the drawbacks of whole-body MRI scans outweigh the benefits of early detection, some experts have found. “Metaphorically, you could go to Vegas and win the jackpot,” Davenport says, “but the average expected result is losing money, especially if you’re gambling regularly.”

Sun, the ER doctor, had no family history of cancer. He exercised, ate a plant-based diet, and was “super healthy.” When his Prenuvo scan found the cyst—and a more targeted follow-up MRI showed it in more detail—he knew it might still mean nothing. Even so, he persuaded his doctors to expedite surgery to avoid “spending months stewing and ruminating” about worst-case scenarios.

His care team prepared to potentially remove a small part of his right kidney as a precautionary measure. Every expectation was that it would be benign.

When Sun woke up five hours later, he learned the kidney was “completely gone,” he says. The surgeons removed it because they thought the surface looked malignant.

Sun had no complications from surgery, but at 37, he recognizes he’s less vulnerable than some. Older people tend to be less protected due to age-related changes. Having an unnecessary surgery, which could involve serious consequences, is one risk Davenport cites. “Every time someone does an endoscopy, biopsy, or surgical procedure, risks include a bleeding complication or difficulty with anesthesia,” he says. “It can be life threatening.”

Davenport is underwhelmed by the potential benefits, at least for people without any known health issues. About 15-30% of whole-body MRIs show a red flag, but the vast majority of these concerns end up being nothing to worry about. Even when cancer is ultimately removed, it’s often unclear if it would’ve grown or how fast. “Both patient and doctor are happy because they found cancer early, but 15 years later, when you look at the data, it didn’t improve mortality,” Davenport says.

Larger studies are needed, and several are trackinghow interventions based on whole-body-MRIs contribute (or not) to longer, healthier lives. But researchers must follow people for decades to see a survival benefit. Without more evidence, the leading associations of radiologists, the American College of Radiology and the Radiological Society of North America, haven’t recommended whole-body MRIs for the average healthy person.

Another risk is giving someone a false sense of reassurance after full-body MRIs come back clean. It’s a mistake to then assume that health screening measures, like colonoscopies, aren’t necessary. Full-body MRIs show some organs better than others. “The kidney and liver are very well depicted,” Daldrup-Link says, but the scans less reliably image colon cancer, lesions in the prostate, and small lung cancers. “That’s a big caveat,” Daldrup-Link says.

Durand agrees, while noting that recommended screenings can’t catch everything. “Whole-body MRIs don’t replace primary care doctor visits and consensus-based screenings. They’re on top of these screenings.”

Sun was shocked and worried to learn his kidney was removed. “What if they literally took out my kidney for no reason?” he kept thinking.

Yes, the organ had looked diseased, but a biopsy would need to confirm that. Thus began a week of agonizing over the possibility that it wasn’t cancer. “That is the danger of doing full-body MRIs,” Sun says.

The results of full-body scans are frequently hard to interpret, difficult to act upon, and detrimental to mental health, Davenport says. “Someone who identifies as a normal, healthy person is quickly converted into a patient,” even though they might be perfectly healthy. “This creates anxiety that is meaningful and measurable.”

A week after surgery, Sun got the call. “I don’t know what possessed you to get that scan,” his surgeon told him, “but you saved your life. It was an aggressive cancer.”

Sun felt reassured. At least his kidney hadn’t been robbed without justification. Then confusion and sadness sunk in as his identity suddenly reconceptualized as both a cancer patient and survivor. How could this happen to a healthy 37-year-old?

Maybe a line can be drawn in the sand dividing people with high cancer risk and people without such risk, but it’s wind-swept and covered with footprints. Cancer is often caused by interactions between various genes and environmental factors, and many of them aren’t well understood. “We will never know with 100% precision which patients are most at risk,” Davenport says.

The mysterious rise of cancer in young adults is the subject of myriad theories and debates. Relatively few people have been diagnosed with genetically-rooted cancer syndromes, yet scientists are “constantly discovering new types” of these syndromes, Daldrup-Link says.

To better understand your personal risk for cancer and other diseases, speak with your doctors about family history. Regular blood tests can show elevated markers associated with diseases and genetic risks for cancer and heart disease. (Sun’s test, however, showed no genetic risk.) This information may warrant individualized, targeted screening, including detailed CTs of relevant organs.

Meanwhile, the technology for whole-body MRI scans continues to improve. “The genuine interest to want to know what’s inside the body is totally understandable,” Davenport says. “Whether you get a whole-body MRI is a personal decision, but it’s important to consider the risks as well as potential benefits.”

Happy Passover

Classier Times

Reinaldo Herrera, Arbiter of Style for Vanity Fair, Dies at 91

Both old school and Old World and married to a celebrated fashion designer, he helped define Manhattan’s high life for many years.

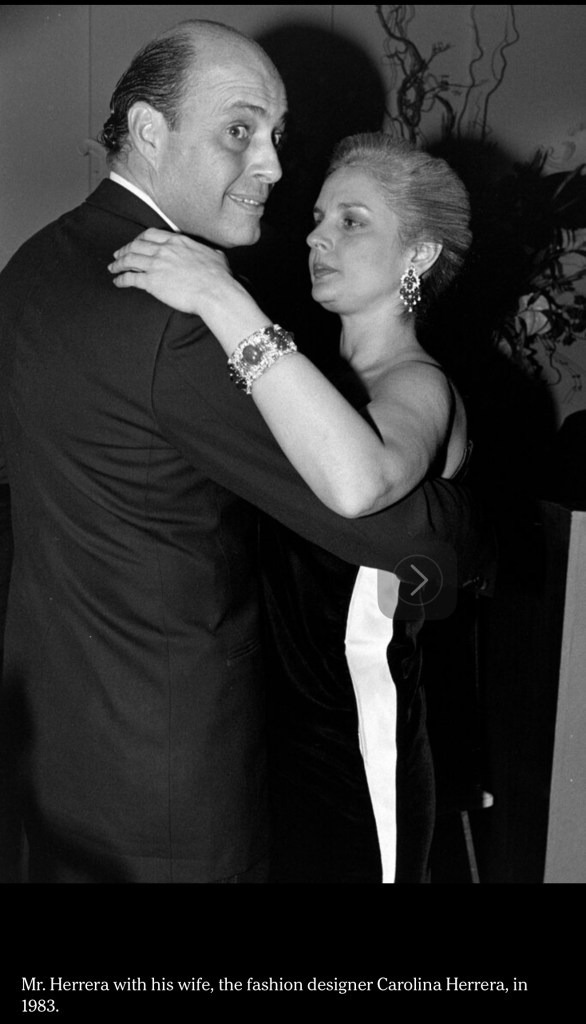

Reinaldo Herrera, a dapper Venezuelan aristocrat, married to the fashion designer Carolina Herrera, whose social connections made him an indispensable story wrangler and all-around fixer for Vanity Fair magazine, where he served as a contributing editor for more than three decades, died on March 18 in Manhattan. He was 91.

His daughter Patricia Lansing confirmed the death.

Mr. Herrera was born into South American nobility and grew up between Caracas, Paris and New York. After attending Harvard and Georgetown Universities and working as a television presenter for a morning show in Venezuela, he joined Europe’s emerging jet set, mingling with Rothschilds and Agnellis, Italian nobles and British royals.

Princess Margaret, Queen Elizabeth II’s sister, was a pal. He dated Ava Gardner and Tina Onassis, the first wife of the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle, and in 1968 he married his younger sister’s best friend, Maria Carolina Josefina Pacanins.

He was old school and Old World. He wore bespoke suits with immaculate pocket squares; his jeans were always crisply pressed. His manners were impeccable. He spoke classical French without an accent. Graydon Carter, a former editor of Vanity Fair, described his voice as a combination of Charles Boyer, the suave French actor, and Count von Count, the numbers-obsessed Muppet.

ImageMr. Herrera with his wife, the fashion designer Carolina Herrera, in 1983.

By the late 1970s, the Herreras were part of the frothy mix that defined Manhattan society at the time — the socialites, financiers, walkers and rock stars, along with a smattering of politicians, authors and artists, who dined on and off Park Avenue and danced at Studio 54. (Steve Rubell, the club’s rambunctious co-owner, used to slip quaaludes into Mr. Herrera’s jacket pockets; Mr. Herrera, who loved a party but not those disco enhancements, would throw them out when he got home.) Robert Mapplethorpe photographed the couple for Interview magazine, Andy Warhol’s monthly chronicle of that world.

In the early 1980s, a few months after Tina Brown became editor of Vanity Fair, Bob Colacello, a former Interview editor who was then writing for Ms. Brown, brought Mr. Herrera into the office. He was so entertaining, as Ms. Brown wrote recently in “Fresh Hell,” her Substack newsletter, that she hired him immediately.

Ms. Brown knew the news value of a man like Mr. Herrera, the currency of his social chops. He called her “Fearless,” short for “fearless leader,” and, she wrote, “like a golden retriever in a dinner jacket,” he brought her dispatches each morning from the evening’s parties.

He was good with the wives of despots, who were among his intimates; he once persuaded Imelda Marcos, the disgraced former first lady of the Philippines who was then in exile in Hawaii, to sit for a profile written by Dominick Dunne. (Mrs. Marcos was not pleased with the result.)He was able to nail down an interview with the Palestinian leader Yasir Arafatfor the writer T.D. Allman on Mr. Arafat’s private jet because Mr. Herrera and Mr. Arafat shared a barber.

Mr.Herrera, right, in 2005 with Bob Colacello, a writer for Vanity Fair.

Mr. Herrera, right, in 2004 with Graydon Carter, who took over Vanity Fair in 1992.

He performed the same service for Mr. Carter when he took over the magazine in 1992. In 1996, Mr. Carter was eager for the writer Sally Bedell Smith to pursue a piece about the Rothschilds, the European banking family, and he thought the funeral of one of its scions, who died by suicide at a hotel in Paris that July, might be the way in. But how to sneak Ms. Smith into the service? Mr. Herrera knew just what to do.

“Hire a small dark car with a driver, wear a simple black dress, a plain black hat, black gloves, all for ‘the look.’ Just walk in and be yourself,” he told Ms. Smith. It worked.

“The only time we had a tiff was when Christopher Hitchens did a story that was hard on Mother Teresa,” Mr. Carter said in an interview. (In 1995, Mr. Hitchens excoriated Mother Teresa, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 and would later be canonized, as a “Vatican fundamentalist,” lover of dictators and “presumable virgin,” among other things.) “Reinaldo stormed into my office and declared, ‘You’ve gone too far. I’m canceling my subscription.’ I said, ‘You can’t do that, you’re on the comp list.’”

Mr. Herrera also taught Mr. Carter how to entertain Princess Margaret (bottles of Famous Grouse whisky and barley water were important) for a dinner he persuaded Mr. Carter to hold for her at his apartment, saying she would be helpful in promoting the European edition of the magazine.

Since protocol, as Mr. Herrera had patiently explained, required that no guests could leave before the princess, and since she stayed past midnight, the evening was a bust, Mr. Carter wrote in his just-published memoir, “When the Going Was Good.” Once everyone was released, he added, “The relief on the faces of the other guests,” among them the entertainment mogul Barry Diller and Peggy Noonan, the Reagan speechwriter and Wall Street Journal columnist, “was the sort of look that survivors of a difficult airplane landing have when they step out onto the tarmac.”

Mr. Herrera was very good with royals. He used his title — he was a marquis — only in countries that had functioning monarchies. “We didn’t know he had a title until we launched the U.K. edition of Vanity Fair,” Mr. Colacello said.

Mr.. Herrera at a charity event at the United Nations in 1988.

But the Vanity Fair writer Amy Fine Collins recalled a time when Mr. Herrera was stumped by a queen.

It was a committee meeting, sometime in the early 1990s, of the International Best Dressed List, an annual tradition created in 1940 by Eleanor Lambert, the influential fashion publicist. “I do remember there being a bit of confusion among Reinaldo and his cohort when someone mentioned Queen Latifah,” Ms. Fine Collins said. “Was it possible there was a royal they hadn’t met?”

He was good with protocol in all sorts of areas, as the Rev. Boniface Ramsey recounted at Mr. Herrera’s funeral Mass at the Church of St. Vincent Ferrer on Lexington Avenue. Father Ramsey recalled being corrected by Mr. Herrera, an ardent Catholic, who pointed out that the yellow and white Vatican flag outside the parish was hanging upside down.

Mr. Herrera shone at parties, and he believed that a successful evening should always include a controversial figure. He relied on friends like Claus von Bülow, who was acquitted of the attempted murder of his heiress wife, to bring the requisite chemistry. “Claus is a great catalyst,” he told The New York Times in 1987.

He noted that his dream dinner party would include Ivan Boesky, the corporate raider charged with insider trading, and Jean Harris, the headmistress who murdered her ex-lover, Herman Tarnower, the inventor of the Scarsdale Diet — though both were unavailable, since they were in prison at the time.

Charlotte Curtis of The Times once described the Herreras as “hopelessly civilized.”

Reinaldo Herrera Guevera was born on July 26, 1933, in Caracas, the eldest of four children of Maria Teresa Guevera de Uslar and Reinaldo Herrera-Uslar, otherwise known as the Marques de Torre Casa. Young Reinaldo grew up in the family home, Hacienda La Vega, which was built in 1590 and is apparently the oldest continuously inhabited house in the Western Hemisphere. He graduated from the St. Mark’s School, in Southborough, Mass., and studied history at Harvard and Georgetown.

In addition to his daughter Patricia and his wife, Mr. Herrera is survived by another daughter, Carolina Herrera Jr.; his stepdaughters, Ana Luisa Bruchou and Mercedes Mendoza; a brother, Luis Felipe Herrera Guevara; 12 grandchildren; and seven great-grandchildren.

“Over the years, I came to see Reinaldo’s impeccable comportment as a moral quality,” Ms. Brown wrote in her newsletter. “He felt it was on him to elevate the room and leave people feeling better about themselves.”

Penelope Green is a Times reporter on the Obituaries desk. More about Penelope Green

RENOWNED ART COLLECTORS LIST TROPICAL MODERN ESTATE IN CORAL GABLES FOR $16.7 MILLION

We know the owners. We are on the Board of Fountainhead Arts together. Everyone who has ever seen the house says it’s a dream home. I put this in my blog because it’s not very often you get to see something so glamorous.

Prominent art collectors and esteemed New York attorney Ian Krawiecki Gazes, whose friends include Keith Haring, alongside his husband, Serge Krawiecki Gazes, have unveiled their luxurious Coral Gables mansion to the market, priced at $16,700,000. Nestled within the prestigious Ponce Davis neighborhood at 4780 SW 86th Terrace, the tropical modern masterpiece was envisioned by the acclaimed architect Alberto O. Cordovez and is listed with Lourdes Alatriste of Douglas Elliman.

The residence spans over 12,000 square feet on a generous one-acre lot, offering seven bedrooms, eight bathrooms, and an array of upscale amenities. Features include wood paneling, limestone floors, a state-of-the-art kitchen equipped with Wolf appliances, and a 200-bottle capacity wine cellar. The outdoor area showcases a stunning 40×15 infinity pool, complemented by a fully equipped gym and a three-car garage with potential for lifts. Smart home automation ensures seamless control of lighting, climate, and security, epitomizing modern luxury living.

A legacy of art and culture, the Gazes duo is celebrated not only for their professional achievements but also for their profound contributions to the art world. Their journey as collectors commenced in the early 1980s in New York’s East Village, where they immersed themselves in the vibrant art scene alongside luminaries like Keith Haring. Their collection, which began with a Keith Haring print from his ‘Fertility’ series (1983), has since flourished, reflecting their dedication to supporting emerging artists and capturing diverse cultural narratives.

Images via Element Image